‘This military education is a darned good thing for me. But I suspect life has a good many blows in store for me yet, else Nature would not have endowed me with so much inner power.’ This is from the diaries of Otto Braun, a precociously intelligent young man who volunteered to serve in the German army. He was born 125 years ago today, and he died, still only 20 years old, just a couple of weeks after this diary entry.

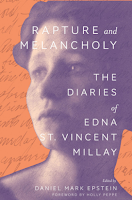

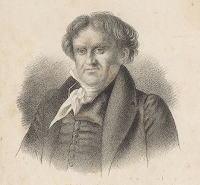

Braun was born on 27 June 1897 in Berlin, the only son of Lily Braun, a writer and women’s rights activist, and her politician husband Heinrich. Considered a child prodigy when young, Otto spent some unhappy years at boarding school, trying to escape at least once, but was mostly educated at home by private tutors. With the outbreak of war in 1914, he joined the army, fighting on the Eastern front until he was wounded in 1916. The injury meant he could not return immediately to active service, and was employed instead by the military section of the Foreign Office. Finally returning to the front line, he was killed by a shell in April 1918.In 1924, Alfred A. Knopf brought out The Diary of Otto Braun as edited by Julie Vogelstein and translated into English by Ella Winter. This is freely available to read at Internet Archive. The book is, in fact, a collection of Braun’s letters and poems as well as diary entries. A ‘Biographical Note’ is barely a page long, so brief was his life.

In her introduction to the texts, Vogelstein says:

‘Besides historical, philosophical, political and military writings of greater or lesser magnitude - complete and incomplete, or merely outlined - there were found among [Otto Braun’s] papers a fragment of a novel, a great number of poems, and twenty-six diaries with regular entries from his seventh year until two days before his death. From these, and from over a thousand letters which we had at our disposal, his father and I made the following selection. The mass of material, and the necessity for keeping the book within reasonable bounds, severely restricted our choice.

None of the entries were intended for publication; Otto Braun was very indignant when one of his poems was printed in a periodical while he was at the front. If the poems are to be regarded as written under an inner necessity without a thought of publication, how much more so is this the case with his diaries. “In order to account to myself, so as to be absolutely honest with myself,” thus he once described his need for this form of confession. Though they are not in literary shape, we have faithfully reproduced all the MSS., and have only corrected obvious slips of the pen.’

Here are several extracts from Braun’s diaries.

20 January 1910

‘It is curious that in the darkness one can see even the tiniest glow, while in broad daylight it is difficult to see the biggest fire; I believe the same is true of human beings.’

10 February 1910

‘I had a very interesting talk with father this morning. There is so much which leaves me unsatisfied at present. What is the purpose of Man, what is his origin? Where does all Life spring from, where do all things start?’

1 June 1911

‘It is not the ascetic, to my mind, who is furthest from becoming a profligate and a voluptuary, but the man to whom this sort of behaviour does not even occur, and who can, therefore, indulge in pleasures, even to excess, without the slightest fear of becoming a profligate.’

5 June 1911

‘Wilhelm Meister. Death of Mignon. How wonderful it is that just at the very moment at which Wilhelm abandons himself to the bourgeois serenity, embodied in Teresa, Mignon dies. I have been thinking a great deal about all these things, so much so that I must let them grow clear now, like my impressions of Florence; I am not afraid that they will vanish or grow cold.’

1 April 1915

‘To-day, in front of the sergeant-major and some N.C.O.s the captain shouted at me, without any reason, in a way that I don’t wish to describe further. Such complete lack of control in an officer was very painful. Every day I grow more calm, and, I may say, more serene, in the face of such behaviour, yet these scenes leave something worse than a bad taste in the mouth, because, completely defenceless as I am, they slowly but surely undermine my moral powers of resistance, which are bent on fighting, and not at all on meek forbearance. I know people here in the squadron who have gone to pieces through the behaviour of the company commander, and that alone. Even if there cannot be the faintest possibility of his breaking me, nevertheless I will try now, come what may, to get out of his company. Lieutenant C. advised me strongly not to file a complaint, as the captain would be put in the right any way. There’s little doubt about that, but the friendly advice I had hoped to get from Lieutenant C. was not forthcoming either.’

17 April 1915

‘The sergeant-major received me with the words: “Well, Braun, you’ve managed it. And I too (?). You will not accompany us to-day, you are ordered to the Signals Section in Lodz.” I almost fell from the clouds, was overjoyed, of course, to get away, but at first rather appalled at the idea of Lodz. Put away all my dirty army kit and reported to the major and captain.’

27 July 1915

‘Beautiful weather; went on fitting up the telegraph cable. The whole time I was most excited and thought out thrilling adventures. Suddenly I got the news that I must return at once as I was transferred to the 21st Chasseurs. That is good. I shall now get to know all there is to know of the war, the danger and the terror; it had to be. My dreams this morning were glorious, glowing; may the gods to whom I pray, the spirit of my forefathers that floats over me, my own strength which I feel within me, grant that I be successful. Hope and faith, desire and will, are my guides, and so I will tread this path cheerfully and securely, filled with that confidence which has always been my support.’

24 March 1918

‘Along the Vosges to Colmar. Beautiful sunny journey. The ancient culture of these parts permeates every village in a most pleasing manner. On a hill to the left towers the gigantic ruin Drei Ahren. In Colmar the streets, squares, yards and a delightful town hall make very charming pictures. Everything grows naturally, but is trimmed and cultivated with wisdom and understanding. One could compare the work of these Gothic architects of cities with that of a sensitive gardener. The deepest impression as regards art was made on me by the interior of St. Martin, an extraordinarily harmonious structure, in which the effect of light has been treated with the utmost skill. Suddenly the communiqué - Peronne taken, the Somme crossed. Everything else vanished. What is to be our fate?’

6 April 1918

‘This military education is a darned good thing for me. But I suspect life has a good many blows in store for me yet, else Nature would not have endowed me with so much inner power to throw off unpleasant things, always to see the best, and never to despair; nor would she have given me so great an urge to assert my individuality, nor the capacity I have, not only to overcome all petty and degrading things, but also to transform them into good, with the help of my Amor fati.’

11 April 1918 [just two weeks before his final entry and his death]

‘In the Field. I received definite news that Kurt Gerschel has fallen. Thus are they all torn away, those that were any good, that were young, courageous and full of hope in the future. He was such a frank, fresh, clean fellow, honest and straight as but few are, such a lovable being! A real lesson to Anti-Semites, brave and proud and true. May he rest in peace.’