‘On our takeoff today we had a tire blow out - the right main gear tire, but it went out after we cleared the field or rather just as we left the field. We went on to the target knowing that we had a rough landing and perhaps a crack up waiting for us on our return.’ This is from a diary kept by US Presidential Nominee George McGovern during his Air Corps days in the Second World War. In the same diary entry, McGovern, who was born 100 years ago today, goes on to explain how he managed to land ‘O.K. without damaging the plane in the least’.

McGovern was born on 19 July 1922 in Avon, South Dakota, to the local pastor and his wife. He was schooled locally, developing an enthusiasm for debating, and then enrolled at Dakota Wesleyan University in Mitchell. In mid-1942, he enlisted in the US Army Air Corps, flying many combat missions in Europe (earning himself the Distinguished Flying Cross). He married Eleanor Stegeberg, and they would have five children together. He was discharged from the Air Corps in mid-1945; he then returned to Dakota Wesleyan University, graduating in 1946. He earned a Ph.D. in history at Northwestern University, Evanston, and later taught at his alma mater.McGovern was active in Democratic politics from about 1948, and by 1957 had been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. After losing an election for a Senate seat in South Dakota in 1960, he served for two years as the director of the Food for Peace Program under President Kennedy. He won election to the Senate in 1962 and was reelected in 1968. By then he had emerged as one of the leading opponents to US involvement in Indochina.

McGovern helped enact party reforms that gave increased representation to minority groups, and supported by these groups he won the Presidential Nomination. However, he failed to hold onto many traditional party supporters, and the incumbent Richard Nixon was able to defeat him by a sizeable margin in the 1972 presidential election. McGovern was reelected to the Senate in 1974, though lost it in 1980. After a return to lecturing, he declared himself a candidate for the 1984 Democratic Presidential Nomination, but dropped out after the Massachusetts primary.

In April 1998, President Bill Clinton nominated McGovern for a three-year stint as US ambassador to the UN Agencies for Food and Agriculture, serving in Rome. In 2000, he set up - with fellow former senator Robert Dole - the Congress-funded International Food for Education and Nutrition Program. In 2001, McGovern was appointed as the first UN global ambassador on world hunger by the World Food Programme. He continued to campaign on political issues, and to write political/history books, not least his last, a biography of Abraham Lincoln. He died in 2012. Further information is really available from Wikipedia, Encyclopaedia Britannica or the US Congress website.

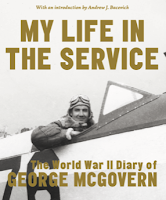

There is no evidence that McGovern was a diarist, but for a brief period, during the war, he kept a lively journal. This was only published posthumously as My Life in Service: The World War II Diary of George McGovern (Franklin Square Press, 2016). The publisher says: ‘[The book] features a facsimile of the diary George McGovern kept from his first days of basic training until the end of the war. Hastily jotted down in his exacting hand whenever he had the impulse to put his thoughts on paper, the pages convey the immediacy of McGovern’s wartime experiences. Each lined sheet is decorated with illustrations, alongside aphorisms on battle and democracy from some of history’s greatest minds. This document powerfully evokes an era, while it predicts the man George McGovern would become.’

Publishers Weekly says: ‘The bravery McGovern demonstrated in wartime, displayed in this unique diary, was mirrored in his service of over two decades in the House of Representatives and Senate, in his 1972 campaign for President, and in his drive to speak out against the Vietnam War, making him a valiant spokesman for a nation in troubled times.’

And a review in the Middle West Review provides some details: ‘The South Dakotan’s diary entries were expansive early on, describing train travel, housing facilities, fellow recruits, rifle training, bayonet practice, gas mask drills, guard duty, weather, and food. As his training continued in several different places in 1943 and 1944, the entries became shorter and less descriptive. Once in combat, McGovern recorded almost every flight in plain, straightforward language, omitting heroics and seldom referring to feelings and emotions or offering comments on the ultimate meaning of it all. Readers get a good sense of the seriousness, sense of purpose, and matter-of-fact dedication that American aviators like him brought to the task.’

There seem to be no previews of the book online, nor can I find any extracts from the diary - other than this one in The Smithsonian.

17 December 1944

‘Another oil refinery today - the one at Oswiecim and Odertal in the Blechhammer flak area. This makes nine missions for me. We really got this one the hard way. On our takeoff today we had a tire blow out - the right main gear tire, but it went out after we cleared the field or rather just as we left the field. We went on to the target knowing that we had a rough landing and perhaps a crack up waiting for us on our return. While going to the target we lost our manifold pressure on no. 2 engine but pulled enough power on the other three to go into the target and get back. The air force lost ten ships to fighters and several to flak but we came through without a scratch. When we got back to base I had everybody but the copilot, the engineer, and myself go back to the waist and brace themselves for the landing. We made sure that all the loose objects were tied down securely. As soon as we touched the runway I chopped the throttle on the side of the good wheel and advanced the throttle on the side of the blown tire at the same time holding down the left brake. We made the landing O.K. without damaging the plane in the least. Needless to say old terra firma felt plenty good. My copilot today was Lt. Brown and the bombardier was Lt. McGrahan. These two boys and Sam recommended me for the D.F.C. because of the landing but I don’t feel as though I deserve a medal as yet.’